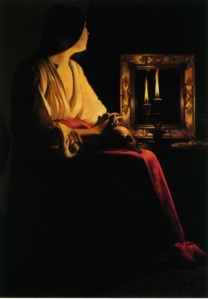

Artist: Georges de la Tour

Artist: Georges de la Tour

Object Name: The Penitent Magdalen

Date: ca. 1640

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 52 1/2 x 40 1/4 in. (133.4 x 102.2 cm)

Classification: Paintings

Credit Line: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 1978

Accession Number: 1978.517

This artwork is on display in Gallery 617

The Penitent Magdalen

1978.517

The subject of this painting by Georges de la Tour is Mary Magdalene, an important figure in Christianity and follower of Christ during his lifetime. In this scene, Magdalene is shown at a moment of contemplation. She looks into a mirror reflecting the light of a candle. She holds a skull on her lap, a symbol of her mortality. Discarded jewelry are said to represent a casting off of material things. The light represents both a focus point for meditation and perhaps a comment on spiritual reality versus artifice or ephemeral existence. In describing the Magdalen paintings, Conisbee et al (1996) quotes Daniel Cramer’s 1624 “Emblematum Sacrorum”, which also features skull and candle imagery, illustrating the biblical quote, “the light shines in the darkness” (John 1:5), and accompanied by Cramer’s verse “sad and pale death cannot frighten whoever becomes familiar with it by frequent reflection; but with Christ in my heart I can overcome it; it is he who will reilluminate my light after death.”

There is an abundance of references on the work of George de la Tour and on this piece in particular. The central catalog record lists a few dozen resources as does the object catalog page on the Museum’s website.

According to Benezit, Georges de la Tour was a French artist of the 17th century only recently discovered to art history in 1915. Critics note that his simplification of form and strict geometry may have been ahead of its time, rejected until rediscovered by Cubist and other modern artists who appreciated this sensibility. Archival research in the early 20th century established that La Tour was in fact quite famous during his time. Born in Lunéville at an unknown date to a baker, he married the daughter of the treasurer to the Duke of Lorraine in 1617 and traveled to Rome around 1613 to 1616. He painted a number of depictions of St. Sebastian, whose help was sought during the plague, which hit Lunéville in 1631. He made his fortune selling paintings to the Duke and collaborating with the French occupying forces who struck Lunéville in 1633. By 1634 Lunéville and presumably much of La Tour’s work was destroyed and he moved to Paris with his wife, where he became a favorite of King Louis XIII. He died in 1652, a very wealthy man (Benezit, n.d.).

The Metropolitan’s painting is one of several created by La Tour, including The Repentent Magdalen (1635-1640) at the National Gallery in Washington, DC (also known as The Fabius Magdalen), The Magdalen with the Smoking Flame (1638-1640) at the Los Angeles Museum of Art and The Madeleine à la Veilleuseat the Louvre in Paris (1640-1645). Other paintings on the Magdalen theme exist in private hands or have been lost, which are listed in Nicolas & Wright’s catalogue raisonné (1974), including an engraving of a horizontal format and copies of the above pieces.

Because so much time passed between La Tour’s life and his discovery by modern art historians, much intrigue surrounds his works. Misattribution of La Tour’s works was common and provenance was often difficult to establish. The Magdalen paintings, particularly the four iconic paintings, offer a case in point. Various experts have attempted to place them within a framework in time and disagree as to the order in which each was painted and what the paintings represent.

The first problem is that the names of the paintings vary depending on the source. In McClintock (2003) and the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Metropolitan’s painting is referenced as The Penitent Magdalene with Two Flames, while in Nicolson & Wright it is The Repentent Magdalen with a Mirror. In McClintock, the “Fabius Magdalen” in the National Gallery in Washington is cited as The Magdalen with a Mirror. Nicolson & Wright refer to the painting in The Louvre as The Repentent Magdalen with a Night Light and describe a second painting of the same name in a private collection. The confusion may be due to the fact that the paintings share similar objects in the composition, including books and a mirror, which appear in three of the four most famous paintings, and a skull, which appears in all four. It is simpler to refer to these works by the provenance or name of the museum where it is currently housed as I have done above.

Iconography is also disputed which contributes to differing opinions around which painting came first in the series. For example, an essay in the Museum’s Notable Acquisitions 1975-1979 describes the work as “…unique in depicting her at the dramatic moment of her conversion…her pearl necklace, bracelets, and earrings have been cast aside….” (Baetjer et al, 1979). In contrast to this, the Benezit article describes the same painting as depicting Magdalene “…beautiful and elegant, not having renounced her jewellery and surrounded by luxury, looking at herself in a mirror.” In this case the candle imagery takes on different meanings, representing perhaps a false path or illusory life versus a true one.

As far as iconography of the images, McClintock (2003, p. 86) notes, “In each, the saint is alone, seated in front of a table in a confined and unrecognizable setting. Each is a nocturne. At least part of a flame is always visible. Each work juxtaposes light and shadow. … The only iconography found in all of the paintings is a skull.” The juxtaposition of light and shadow intensifies the focus on the candle flame, the Magdalen’s face and her bodice. The bare skin of her chest and discarded jewels on the table show that she has removed the trappings of material life. This fits with Pariset’s (1961-1962) notion that the image captures Magdalen at the moment when she has renounced her worldly life and Rosenberg and de L’Épinay’s (1973) interpretation that the image reflects the earliest episode in the her conversion and represents a meditation on the theme of vanity, rather than mortality.

Provenance and Documentation

The Museum acquired The Penitent Magdalen in 1978. According to the 1979 annual report (Berry, 1979), this painting was part of a series of gifts from Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman that included El Greco’s Miracle of Christ Healing the Blind.

References

Baetjer, K. et al. “European Paintings.” Notable acquisitions (Metropolitan Museum of Art), No. 1975/1979 (1975 – 1979), pp. 48-55. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved from http://0-www.jstor.org.library.metmuseum.org/stable/1513628

Berry B. T. et al. (Jul. 1, 1978 – Jun. 30, 1979). “Curatorial Reports and Departmental Accessions.” Annual Report of the Trustees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art , No. 109, pp. 16-47. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved from http://0-www.jstor.org.library.metmuseum.org/stable/40304812

Conisbee, P. et al. (1996). Georges de La Tour and his world. Exh. cat., National Gallery of Art. Washington. pp. 109, 111–14.

Georges de la Tour. (n.d.). In Benezit Dictionary of Artists. Web. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/benezit/B00105038

McClintock, S. (2003). The Iconography and iconology of George De La Tour’s religious paintings, 1624-1650. Lewiston: The Edward Mellen Press.

Metropolitan Museum of Art Central Catalog. (1978). 1978.517. La Tour, Georges de 1593-1652. The Penitent Magdalen. [Catalog record]. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Nicolson, B. & C. Wright. (1974). George De La Tour. London: Phaidon Press Limited.

Pariset, F-G. (1961-1962). “La Madeleine aux deux flammes: Un nouveau Georges de La Tour?” In Bulletin de la Societé de l’Histoire de l’Art Français, pp. 39–44.

The Penitent Magdalen. Georges de La Tour. (French, Sielle 1593-1653 Lunéville). Web. Retrieved from http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/436839

Next: Three Pronged Vajra